Beloved Boulevard Bridge Turns 100

Please make plans to celebrate the Boulevard Bridge Centennial on Saturday November 8, 2025 from 9 to 11 AM.

The Westover Hills Neighborhood Association (WHNA) is partnering with the Richmond Metropolitan Transportation Authority (RMTA) and other organizations to mark this occasion with a free event on the Boulevard Bridge.

This is a unique opportunity for Richmonders to…

Take in the river views as they walk on the historic bridge,

Participate in a Keep Virginia Cozy clean-up,

Hear musical performances by Pay Rent Brass Band and The Hot Seats,

Enjoy treats and coffee from Chiki's Pancakes, Janet's Café & Bakery, and Eddie Rose Coffee,

Witness a short program with city and community leaders to unveil the Centennial plaque. (Around 10 AM at southside bank)

Please spread the word about this celebration of how the iconic Nickel Bridge has connected Richmond over the James River for 100 years!

The Westover Hills Bridge Turns 100

By John M. Coski

The Boulevard Bridge – “Our Bridge” – turns a century old on January 1, 2025. The bridge and Westover Hills were born together. They were two halves of a single scheme to develop and sell real estate on the city’s south side and the eastern fringe of Chesterfield County.

The Commonwealth of Virginia chartered both the Westover Hills Corporation and its subsidiary, the Boulevard Bridge Corporation, in 1922. (In 1949, the Westover Hills Corporation, after selling all of its lots, dissolved itself, and transferred its assets to the Boulevard Bridge Corporation.)

In November 1922 the Boulevard Bridge Corporation issued a long letter “To the Public” explaining its plan and its vision: “While the primary object of our proposition is to enhance the value of real estate on the Southside, both in and near the city, in part of which some of our incorporators are interested, the increased revenues from taxes both on the bridge and real estate, the dedication of very extensive rights-of-way, both in and out of town, for beautiful drives, the enhancement of an increased accessability [sic] to the parks and the charming and beautiful residential districts made available, AND ALREADY LAID OUT BY THE DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC WORKS, render the proposition of very great advantage to Richmond and all its people.”

Although the Boulevard Bridge was a private venture to be built without cost to the taxpayers, the Corporation planned it in conjunction with city officials and built it to provide access to local parks and to a proposed 5-1/2-mile riverside drive. The corporate charter explicitly allowed the city to assume control of the bridge at two-thirds of its cost within five years of its completion. To pay for construction, a toll would be necessary – but only as a temporary expedient.

As of 1922, the only bridges crossing the James at Richmond were the Mayo Bridge and the notoriously “rickety” 9th Street bridge from downtown to Manchester. The Boulevard Bridge would provide easy access between southside and the city’s fast-growing west end.

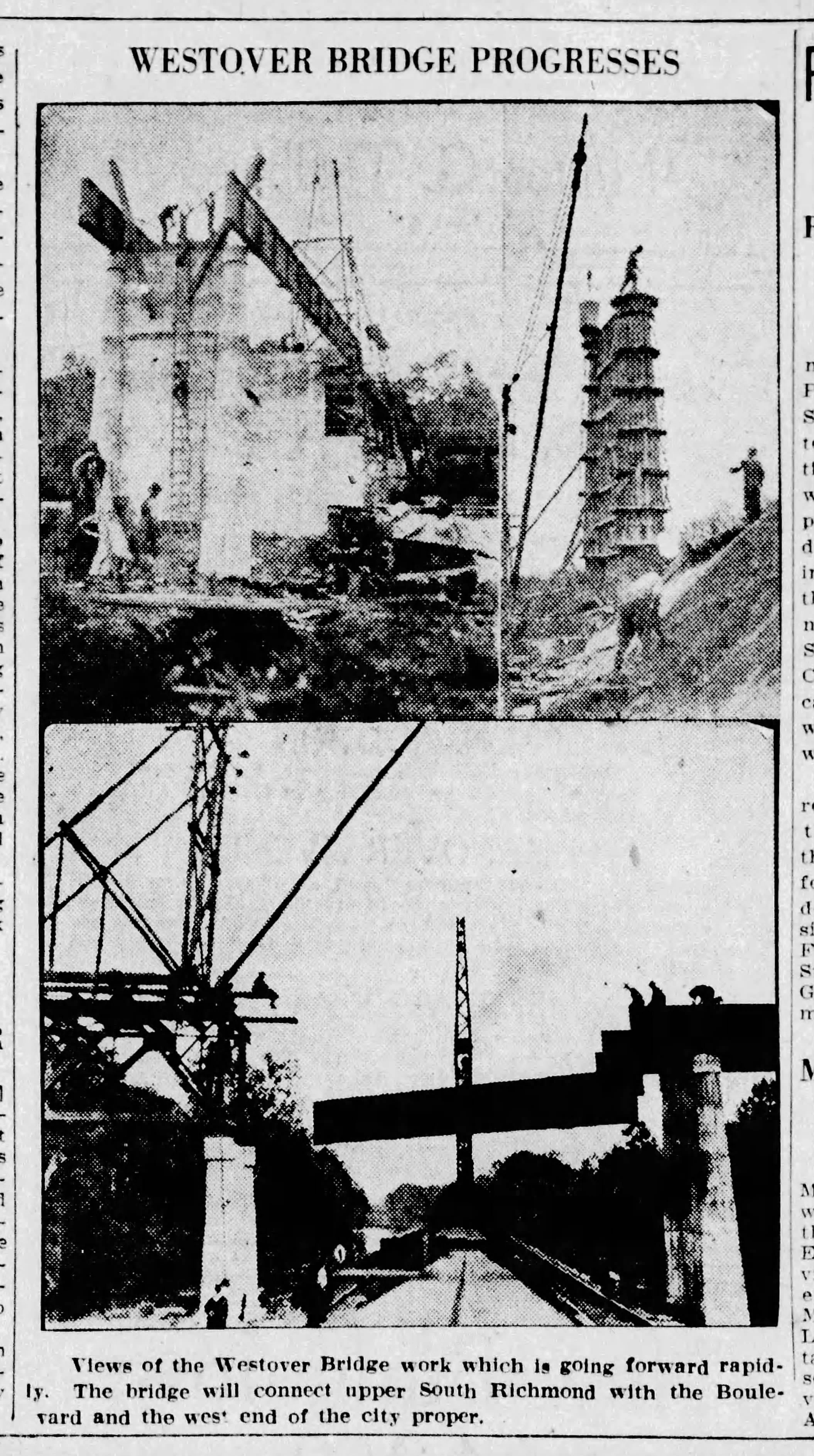

The Atlantic Bridge Company conducted preliminary work at the site in June 1923 and began construction in earnest in November. The cost of the 2,100-foot long and 28-foot wide bridge swelled from $250,000 to $270,000.

On Christmas Eve, 1924, the Boulevard Bridge Corporation issued a public invitation to use the bridge without charge between the grand opening on New Year’s Day, 1925, and January 4. An estimated 5,000 cars and several hundred pedestrians crossed the bridge on the last free day.

The toll on what is still known colloquially as the “Nickel Bridge” was originally a dime. Alternatively, drivers could purchase for $10 a “small ornamental enameled brass badge” – good for the calendar year – to be placed on the front of cars, small trucks, or light one-horse wagons.

Additionally, free passes, good for ten years, would be issued to Westover Hills residents – solidifying the continuing perception of the Boulevard Bridge in the neighborhood as “Our Bridge.”

The bridge proved immediately successful and profitable, used heavily for commuter and “tourist” traffic. The Corporation obtained permission to post signs on the city’s north side directing drivers to Petersburg via Boulevard and Byrd Park” across the bridge, boosting traffic and revenue, and earning the ire of downtown merchants. Bridge revenue also benefited from the months-long closure of the 9th Street bridge in 1930.

Over the ensuing decades, the “temporary” tolls and the free passes for Westover Hills residents that were to be good for ten years continued. Similarly, the city’s anticipated takeover of the bridge was discussed, then delayed, deferred, or derailed in 1941, 1945, 1956-1957, 1959, 1960-1962, 1966, and 1968. “’Do you want to buy the bridge or don’t you?’” Eppa Hunton IV, attorney for the Bridge Corporation, testily asked City Council in 1959.

Among the sticking points in the purchase negotiations were disagreements over continuing the toll and the Westover Hills exemption from the toll. Councilman Robert J. Heberle – a Westover Hills resident – opposed the city’s purchase of the bridge because it would end his neighborhood’s exemption from the toll and because it would delay the construction of another bridge further west. A city attorney confirmed that a public body could not give “special privileges” to Westover Hills residents and they would have to start paying tolls after the sale was consummated. The proposed purchase fell through in 1962 when the Corporation refused the city’s $324,000 offer and the SCC ruled that the James River Bridges Corporation did not have power to condemn the property.

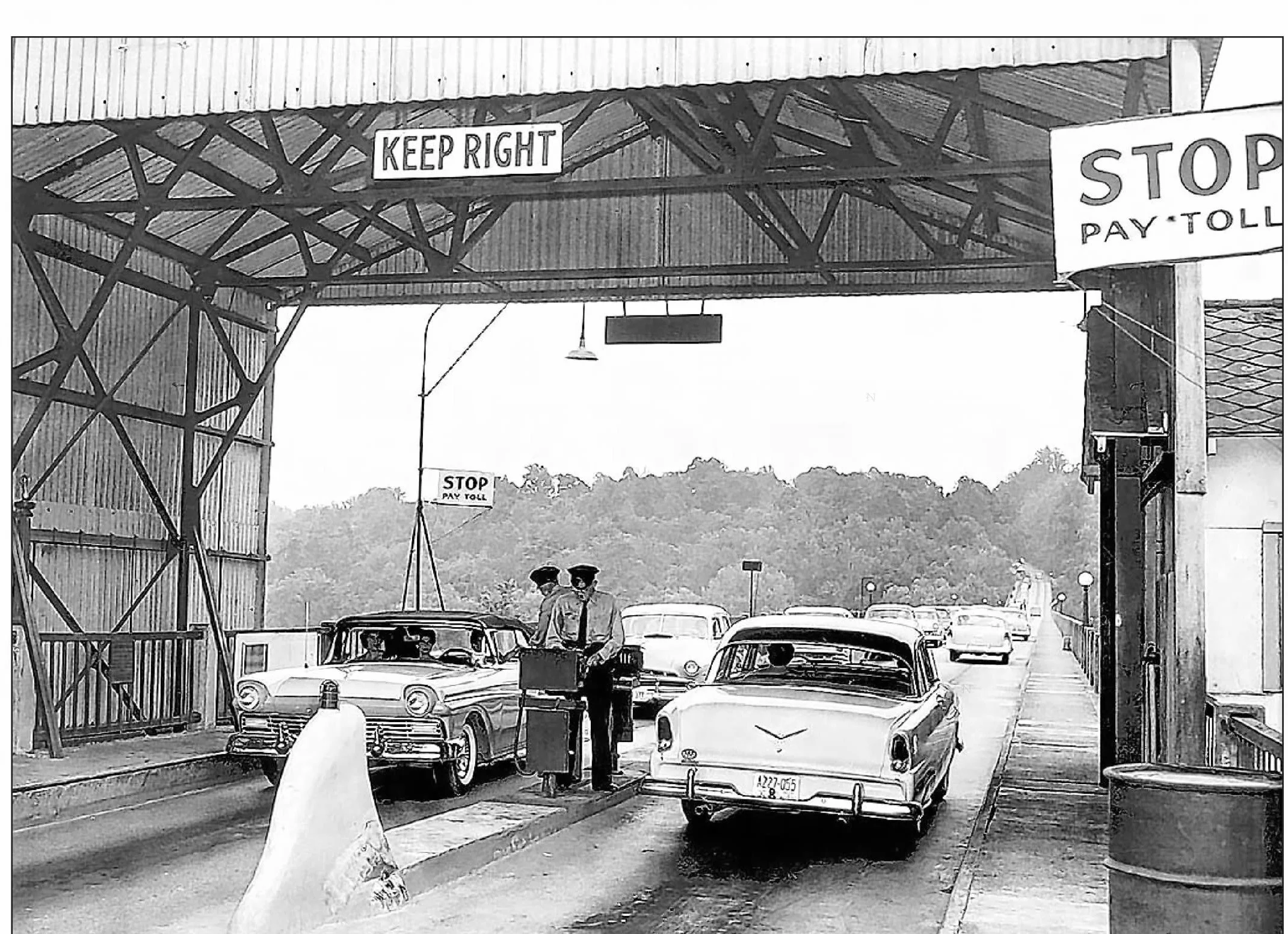

Meanwhile, several activist citizens insisted that the bridge corporation’s franchise to collect a toll had expired in 1955 and that the ten-cent toll represented an unreasonable rate of return on investment. Their lawsuits to stop the tolls failed, but the State Corporation Commission in May 1957 agreed that the bridge had been too profitable and ordered the toll reduced from ten cents to five cents, effective in July. The SCC noted that the toll should be even lower than five cents, but reasoned that making change in pennies would cause traffic back-ups that would vex drivers more than paying a nickel to cross.

As purchase discussions dragged on, the once new bridge grew old and needed improvements and maintenance. The toll collection system needed upgrading. The toll booths located on the bridge deck were quaint, but inefficient. Rush hour commuters typically waited longer than five minutes to cross the bridge. In May 1959, at the city’s behest, the Boulevard Bridge Corporation moved the booths to the Byrd Park side, which reduced the time to just over a minute. Then, from mid-November 1959 to early February 1960, the Corporation closed the bridge for repairs, causing headaches for the approximately 14,350 drivers who crossed the bridge on a typical weekday.

Finally, on July 15, 1969, the new Richmond Metropolitan Authority (RMA) purchased the bridge for $1.7 million and City Council approved the purchase. Vice Mayor (and future Mayor and Congressman) Thomas J. Bliley – who was born and raised in Westover Hills – pushed unsuccessfully for removal of the tolls or the continuation of some kind of bridge passes for Westover Hills-Forest Hill residents. “’In 1970, a toll bridge in the city is a little ridiculous,” Bliley observed.

The RMA made additional improvements in the toll collection system in 1971 (doubling the number of booths) and, in 1973, they raised the bridge toll from five cents to the original ten cents (and raised it to twenty cents in 1988). The famous “Nickel Bridge” toll was only a nickel for 16 of its first 100 years.

Even with modernization, the Boulevard Bridge still had its old-time charm. Beginning in the late 1970s, toll takers William Howard and George B. Stafford handed out lollipops and butterscotch balls to children as their parents paid the toll. Media attention in 1988 led the RMA to ask “Candy Man” Stafford to cease the custom for fear of safety and liability.

Twenty years after purchasing the bridge, the RMA learned that it needed major renovations. The steel supports resting in solid rock were secure, but the deck needed replacement or renovation. The RMA chose renovation at a cost of $6.8 million and opted to close the bridge entirely for up to 16 months.

The original design for the new deck called for two 11-foot wide driving lanes and an isolated 5-foot wide pedestrian sidewalk, all surrounded by solid concrete “jersey barriers.” A citizens committee complained that the jersey barriers would destroy the bridge’s aesthetic and, more importantly, cause a dangerous “tunnel effect” on the narrow bridge. The RMA agreed and redesigned the bridge with metal rails and lampposts

The bridge closed to all traffic on August 17, 1992. Westover Hills Boulevard became a quiet backwater street. It was peaceful for residents, but an inconvenience for the 18,000 daily bridge users, and a financial disaster for Westover Hills businesses. The work was finished months ahead of schedule, and the bridge reopened on November 1, 1993.

The 1992-1993 deck repair was calculated to extend the bridge’s life for another 25-30 years – through about 2023. As we observe Our Bridge’s centennial birthday, we must brace ourselves for the next chapter in its history.